AI is all around you, but you have the right to know

With the advancement of technology, artificial intelligence (AI) has quietly entered hospitals and become an “invisible helper” for doctors’ diagnosis and treatment. From interpreting X-rays and assisting in prescribing medications to organizing patient email responses, AI has greatly improved healthcare efficiency.

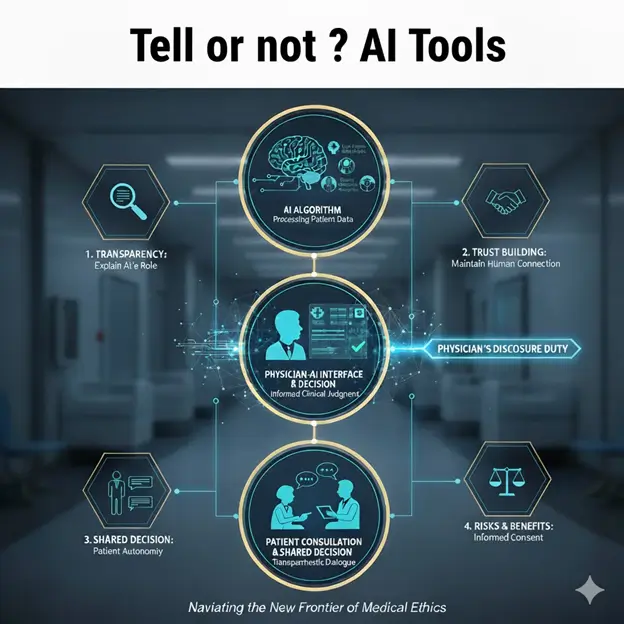

However, the widespread application of AI also raises an urgent ethical question: Do patients need to be informed when hospitals use AI tools to assist in medical decision-making?

According to a recent important article in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), the traditional “informed consent” process usually only requires patients to be informed of important information about treatment, such as drug side effects or surgical risks, and often omits the “auxiliary tools” behind it. However, multiple surveys show that the majority of American adults (more than 60%) have made it clear that they would very much like to be informed if AI is used in their medical procedures.

Faced with patient expectations, legal responsibilities, and trust in maintaining the doctor-patient relationship, medical institutions can no longer turn a blind eye. This article will explain in a simple and easy-to-understand way how hospitals should decide when to “inform”, when to “seek consent”, and how to communicate based on the “AI Disclosure Framework” proposed by JAMA.

Problem: You can’t tell everything “one-size-fits-all”

You may be thinking, since everyone wants to know, why not just say no?

In fact, comprehensively informing every AI tool is both impractical and may have counter-effects:

- Information Overload: There may be dozens of AI tools operating in a hospital. If even the AI that reads the ECG has to explain it specially, the patient will be overwhelmed by too many and unimportant details, and may ignore the really critical information.

- Trust Erosion: Studies have shown that even if AI-generated email responses are more empathetic than those written by real people, patients are less satisfied with the response when they are told “this is written by AI.” Over-disclosure can be counterproductive and cast doubt on the value of the medical profession.

- Potential Algorithmic Bias: If hospitals give patients the right to “opt-out” and not allow AI to use their data, it may lead to insufficient breadth of AI training data in the long run, affecting the accuracy of AI and ultimately harming the public health of a wider range of patients.

Therefore, professional medical leaders must have a more precise and strategic standard for determining the extent of AI disclosure.

Decision-making framework: two keys to judging “what to say or not”

JAMA’s framework tells us that to determine whether to disclose AI to patients, we must answer two core questions: “Is this AI risky?” and “Does the patient have a choice?”

Key 1: How high is the “risk of physical injury” brought by AI?

This assessment requires considering a combination of three elements:

- Potential for AI errors: How accurate is this AI model itself? Is the error rate high?

- The possibility of medical staff intercepting errors: Even if AI makes an error, what are the chances that the doctor or nurse in charge of monitoring will detect and correct the error in time? (People will have “automation bias” due to over-reliance on AI, reducing their vigilance.) )

- How serious is the harm caused by the error: If the AI makes a mistake and is not intercepted, will the physical consequences be minor (e.g., a small medication reminder error) or will it cause serious or even immediate harm (e.g., error in judgment during surgery)?

Conclusion(s): The higher the multiplier of the three elements, the heavier the hospital’s disclosure obligations.

- Example: An AI surgical navigation tool, even if the probability of error is low, once it makes a mistake, the consequences are immediate and serious, then the risk value is high and strict disclosure is required.

Key 2: How much “agency” can the patient exercise?

Autonomy refers to the patient’s ability to act in their best interests after being informed. This is divided into two levels:

1. Can I opt out of AI-assisted therapy? (Option)

- Consent Required: If the patient has practical, clinically feasible alternatives.

- For example, a hospital has introduced an AI-navigated non-autonomous surgical robot. Patients have the option of undergoing traditional non-robotic surgery. At this time, patients have a high degree of autonomy in choosing treatment methods, and hospitals should “seek consent”.

- Neither: If the patient does not have any reasonable alternatives.

- For example: A hospital’s logistics management AI predicts how much blood stock needs to be prepared based on your surgery time. Patients cannot ask hospitals to shut down this operational efficiency AI. Patients have no choice, and the hospital does not need to inform them.

2. Can you change your behavior to protect your own interests? (Actionable Awareness)

- Notification: Even if you can’t opt out of using AI, can patients respond helpfully when they learn about it?

- For example, a doctor’s outpatient record summary is automatically generated by AI. After being informed, patients will check their electronic medical records more carefully to see if there are any omissions or errors generated by AI. In this case, the hospital should “notify” the notification that can prompt the patient to take action.

Practice: Three levels of “inform” in hospitals

Combining risk and autonomy, medical institutions can divide the use of AI tools into three levels and formulate corresponding disclosure policies:

| AI use cases | Risk assessment | Autonomy assessment | Recommended disclosure level | Practical operation principles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High risk/high autonomy | High (mistakes can cause serious injury) | Yes (patient optional alternative) | Consent | Before treatment, clear and concise information must be provided for patients to sign the consent form to ensure they understand and accept AI intervention. |

| Medium risk/actionable autonomy | Medium and low (errors can be corrected, but still need to be noted) | Yes (patients can check or question the AI results) | Notification | Through footer text, website announcements, or simple statements, the AI is informed of participation in the process without the patient’s signature and consent. The focus is on transparency. |

| Low risk/no autonomy | Low (bug impact is minor and easy to fix) | None (not related to patient treatment options) | No need to inform (Neither) | Think of it as a standard internal operational efficiency tool that is not specifically mentioned at the point of care to avoid information distractions. |

Key points of communication: How to “speak” effectively?

When hospitals decide they have to tell, how the information is presented is key. Disclosures must use “simple, specific language” and include the following elements:

- Uses of AI tools: Describe the specific functions of AI (e.g., AI assists in predicting infection risk instead of AI diagnosing).

- The Role of Human Doctors: Emphasizes that AI is only an assistant, and the final judgment and decision-making are still the responsibility of the doctor.

- Institutional Monitoring Mechanism: Explain how hospitals regularly check and monitor the performance of this AI tool, especially for different groups of patients, to ensure fairness and safety.

- What the patient can do: Clearly state whether the patient can opt out or what further tests or inquiries they can request upon being informed.

Governance is a KPI for sustainable development

The application of AI in healthcare is the general trend, promising greater efficiency and more accurate clinical outcomes. However, deploying AI responsibly is not only a technical challenge but also a business ethics and strategic governance.

For leaders and investors in healthcare institutions, a robust AI disclosure framework is not only a legal and ethical obligation to comply but also a key indicator (KPI) for maintaining patient trust. Through this structured “risk and autonomy” assessment, hospitals can avoid the “all or nothing” transparency dilemma and provide the best clinical care while ensuring that patients can exercise their choice over their own treatment on a fully informed basis. Maintaining trust is the most sustainable investment in medical innovation in the AI era.

Mello MM, Char D, Xu SH. Ethical Obligations to Inform Patients About Use of AI Tools. JAMA. 2025; 334(9):767–770. doi:10.1001/jama.2025.11417

This article is based on the article “Ethical Obligations to Inform Patients About Use of AI Tools” published by the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), using Gemini Pro 2.5 for professional interpretation and simplified explanations.